Margarita Zavadskaya

Margarita ZavadskayaPolitical Scientist and Sociologist

How Russia is returning

to totalitarianism

Questions to Experts

We asked 15 experts 3 questions about the future of Russia

The post-Soviet leadership of Russia considered free elections as the basis of its legitimacy. However, learning to vote and organize voting was challenging. The history of “pre-Putin” elections in Russia deserves a separate writeup, with key events including the conflict of 1993, where tanks ordered by the elected president, Boris Yeltsin, fired on the elected parliament (still in office from the last elections in the Soviet Union) in Moscowl, and the presidential campaign of 1996.

Longtime Kremlin watcher and journalist Mikhail Zygar, author of "All Free," provided a succinct subtitle to explain when everything began to go downhill: "The Story of How Elections Ended in Russia in 1996." In that year, Boris Yeltsin won a second presidential term in the second round of the elections, but not without significant media manipulation stoking fears of a return to communism. On New Years Eve of 1999, an ailing and elderly Yeltsin resigned handing power to a young and unknown successor, Vladimir Putin. Overall, the 1990s were marked by collusion with oligarchs, significant financial abuses, and failure to develop the institution of independent elections. Since 1999, Vladimir Putin has been in power, with a four-year break for Dmitry Medvedev's presidency.

In 2001, laws were passed significantly limiting the creation of new parties and parliamentary coalitions. In 2003, before the next parliamentary elections, the Kremlin vividly demonstrated what could happen to those attempting to fund opposition political parties - oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky was imprisoned for 10 years. In 2004, in the wake of a terrorist attack in Beslan, North Ossetia, the election of governors was abolished ostensibly to increase oversight and security, but in reality as a pretext to consolidate more power. Regional leaders were now appointed by the Kremlin. Work was also done with specific politicians: for example, the leader of the Communist Party of Russia, Gennady Zyuganov, nearly lost chairmanship of the party but managed to retain his leadership position with some informal help from the Kremlin, thus strengthening his status as controlled opposition. Protest coalitions and independent politicians were practically barred from real elections - either being denied candidacy for formal reasons or being “dealt with” immediately after the elections. In the summer of 2006, the option to vote "against all" was legislatively removed and the threshold for parties to get seats in the Duma was increased from 5 to 7% of the national vote. Manipulating electoral procedures became one of the hallmarks of Russia’s electoral authoritarianism.

On December 6, 2011, three days after parliamentary elections, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev met with the head of the Central Election Commission, Vladimir Churov. Churov reported on the election results, telling him about an internal office bet that CEC officials had going on the election results. Churov had been the winner - he was only off by 0.2 %. Medvedev responded "you are a magician. Some parties’ leaders call you that.” Churov modestly replied, citing a classic Soviet film adaptation of Cinderella, "I'm only just getting started."

Meanwhile, significant protests, the largest in decades, were unfolding against numerous voting fraud allegations. On election day, December 4, 2011 social media was flooded with videos of various violations, including "carousel voting" and mass transportation of state employees to polling stations. Independent observers faced removal from polling stations. The "Golos" movement documented these violations online through a “Map of Violations,” where they, other observers and ordinary citizens could report on what they saw. A notorious incident involved preliminary voting results from three regions, broadcast on a major federal channel, adding up to an improbable 146%.

The official results read that the ruling party "United Russia" garnered just over 49% of the votes, maintaining parliamentary control. However, international observers, experts, and political scientists believe the actual figure was much lower. The discrepancies were even analyzed through scientific, mathematical methods, revealing significant and obvious errors.

The 2011-2012 protests against election irregularities, posed a serious challenge to the Russian regime, often termed an "electoral autocracy" since the mid-2000s. In December 2011, over the course of several weeks, nearly 100,000 people (120,000 according to organizers) braved -30°C temperatures in Moscow on Sakharov Avenue, demanding a re-vote, acknowledgment of the falsifications, and genuinely fair and publicly supervised elections. Protesters were also angry about the September 2011 announcement that Putin and Medvedev planned to switch places in the next presidential election, the so-called “castling” maneuver, with Putin again running for the presidency and Medvedev as his Prime Minister. The protesters felt that this work-around to the two-term limit on the presidency took away their voice as much as the election falsification did.

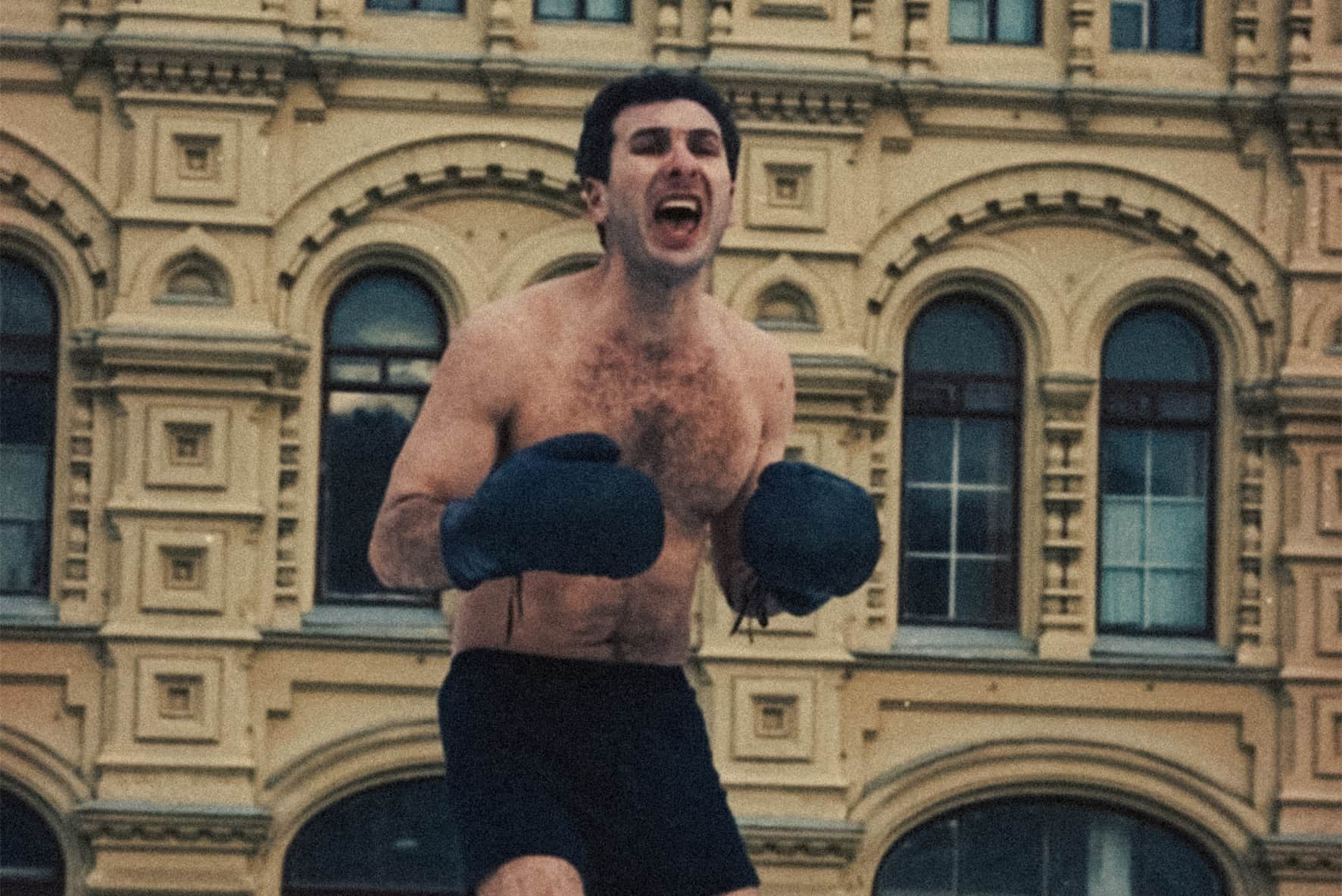

On May 6, 2012, the united opposition forces organized the "March of Millions" in an attempt to express their protest against Vladimir Putin's inauguration following his fraught victory in the elections. The march and rally were coordinated with the local administration, but law enforcement authorities hindered its conduct. For instance, they detained or removed activists from trains who were traveling from other cities. On that day, the protesters marched along Bolshaya Yakimanka Street, but a conflict erupted between them and the police at Bolotnaya Square. Opposition leaders Alexei Navalny and Sergei Udaltsov declared a sit-in strike. The police attempted to disperse the people from the square, leading to clashes that eventually resulted in what became known as the "Bolotnaya case." Out of the 400 detained individuals, criminal cases were initiated against 35, some of which resulted in actual prison sentences. In response to the protests, the Kremlin made some changes to the electoral process, including restoring elections of regional governors and installing cameras in polling places. But none of these had a real impact in restoring free and fair elections.

In 2012, the protest forces attempted to unite, and in October, elections were held for the "Coordination Council of the Opposition" (CCO). Representatives of the opposition ranging from ultra-liberal to communists to extreme nationalists contested the elections, all aiming to challenge the dominance of the "United Russia" party in one way or another. Although the CCO was an unofficial entity, its elections followed a complex scheme. Its creators wanted to emphasize the distinction from official elections, which they were protesting due to falsifications. As a result, the CCO had members with diverse political views, including nationalist Daniil Konstantinov, leftist activist Sergei Udaltsov, politician Alexei Navalny, journalist Sergei Parhomenko, and former Deputy Prime Minister Boris Nemtsov. The CCO operated for a year and then ceased to exist, as the opposition failed to reach a consensus among themselves.

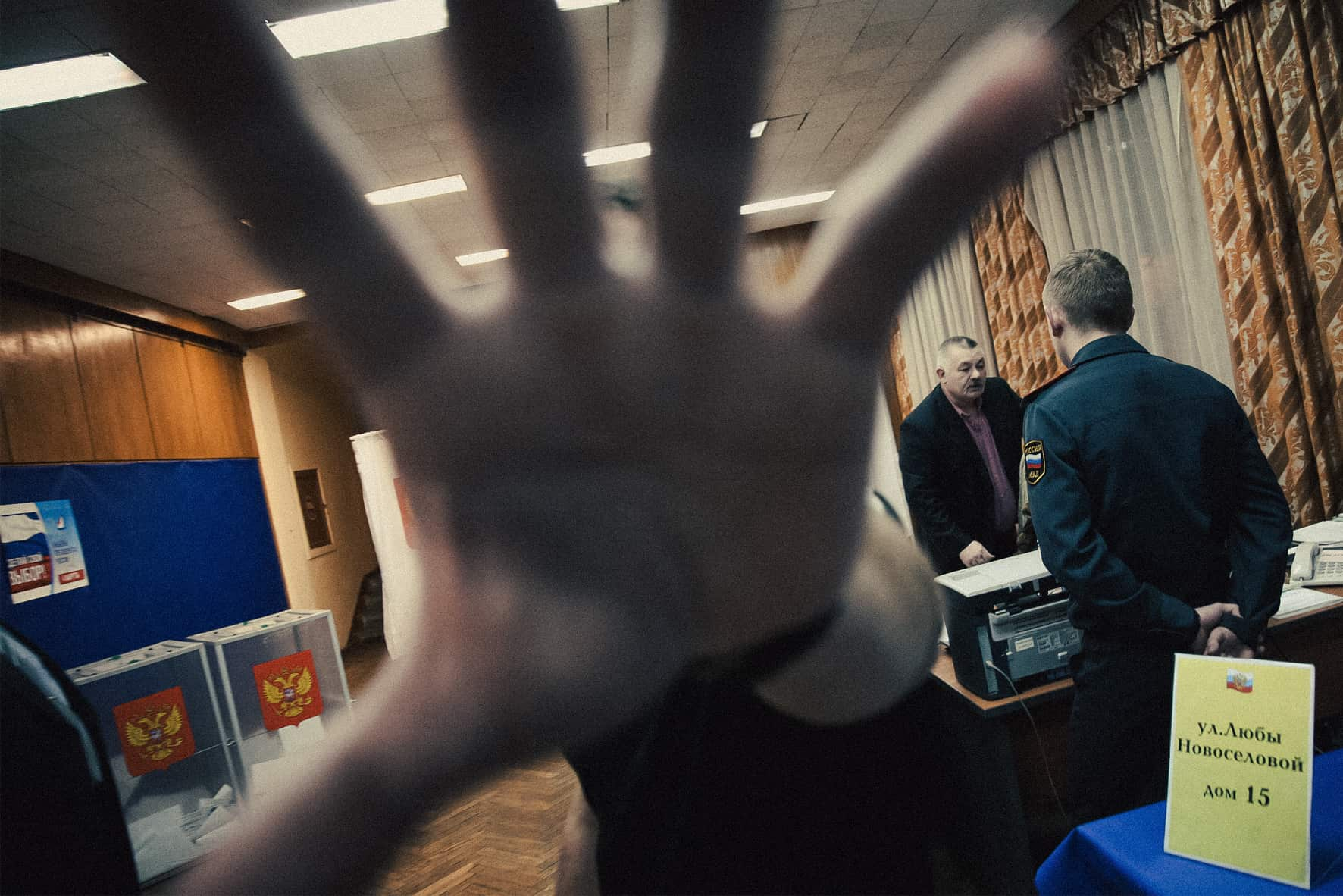

However, there was still growing interest in and attention to the electoral process within society. Even parties that were not entirely opposition-oriented started actively preparing and sending observers to polling stations. Ordinary citizens voluntarily took on the arduous and often risky role of observers, defending their polling stations from falsifications. Observers were physically pushed out of polling stations, beaten, and subjected to other forms of pressure. For instance, in 2015, during the elections for the city council of Balashikha in the Moscow region, observers Dmitry Nesterov and Stanislav Pozdnyakov were beaten when they tried to detain a woman who was stuffing ballots into the voting bin. As a result, Pozdnyakov had to have his spleen removed. These practices continued. In 2020, during the vote on the constitutional amendments, David Frenkel, a correspondent for "Mediazona," had his arm broken while attempting to document violations at a polling station in St. Petersburg.

In other cases, the authorities were willing to experiment, showing their openness and readiness to engage in direct competition with opponents in elections. In 2013, Alexei Navalny, a politician who had previously been convicted in the "Kirovles case", was released from custody at the request of the prosecution. Shortly thereafter, he was allowed to run in the Moscow mayoral elections. Most likely, the Kremlin's plan was to defeat the opposition candidate in the elections, but in practice, the elections nearly went to a second round. Navalny secured second place with 27% of the vote and claimed that the vote count was not entirely fair. During that campaign, the authorities appeared to demonstrate their maximum willingness to compromise and participate in electoral political competition. Navalny’s relative success showed the authorities that open political competition was too dangerous for achieving their preferred outcomes. From then on the political arena became increasingly more constricted.

In 2014, shortly after the annexation of Crimea, government-affiliated political analysts began talking about the emergence of a "Crimean consensus" - a record increase in the ratings of authorities (particularly Putin) attributed to the annexation. In this situation, electoral games seemed like an extravagance to the authorities. In September 2014 on voting day, in all regions holding elections for regional heads, incumbent governors emerged victorious. In most cases, the elections - even in key regions like St. Petersburg - lacked any semblance of intrigue; opposition candidates with some weight and recognition were not allowed to participate. Incumbent governors received between 50% and 90% of the votes, and voter turnout in some cases did not exceed 30%. High voter turnout was not then a priority for the authorities.

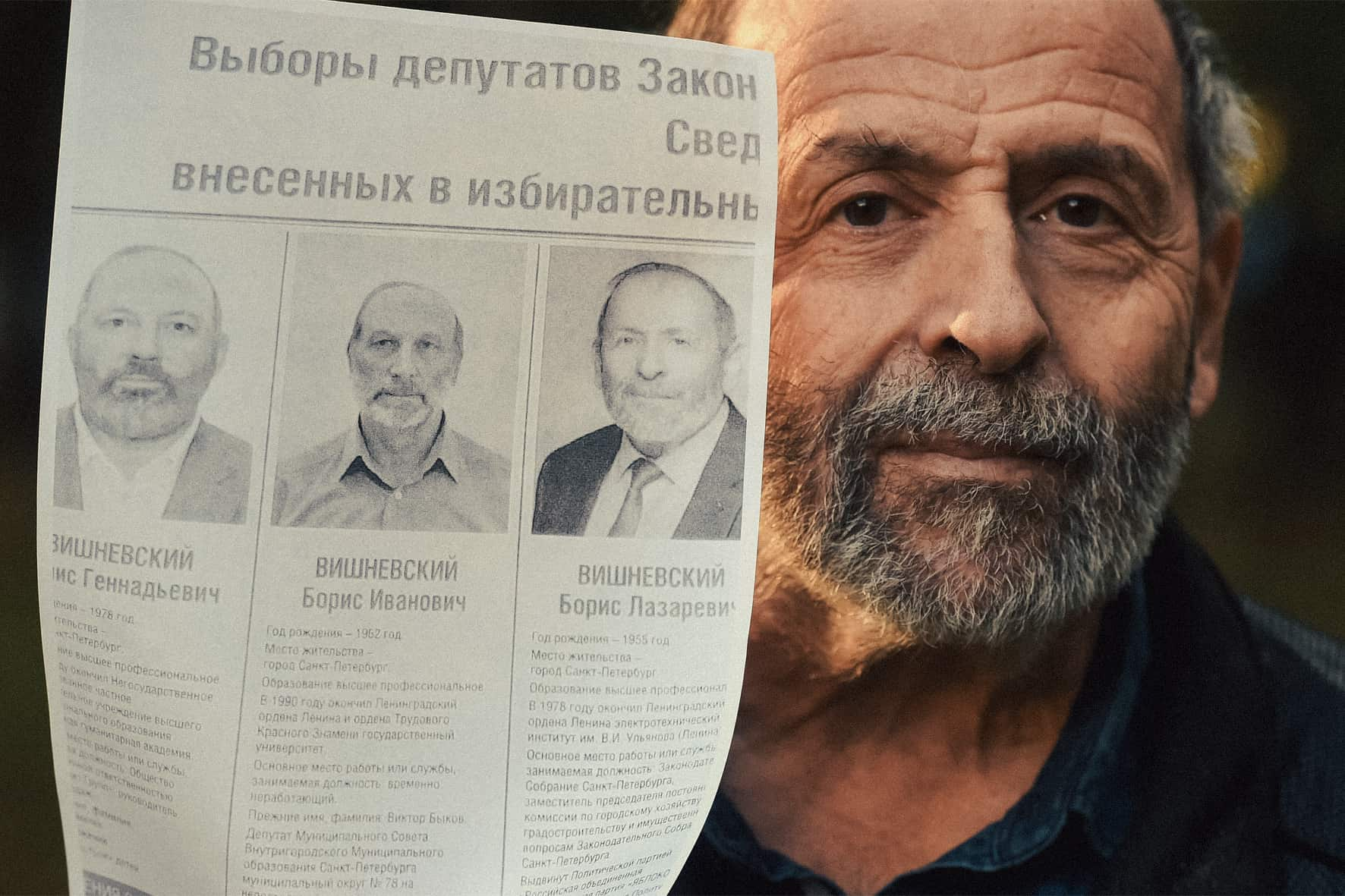

This method of organizing elections appeared to be successful and continued to develop further. The presidential administration openly set KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) for regional authorities regarding the percentage of votes and voter turnout. The local apparatus implemented top-down directives through falsifications, coercion, the distribution of gifts to voters, and effectively barring unwanted candidates. Local methods varied, sometimes getting absurd - for example, in the summer of 2021, during the elections to the State Duma in St. Petersburg, two spoiler candidates were registered against opposition politician Boris Vishnevsky. Both had the same name (one of them changed his name right before the elections) and even visually resembled the opponent. The dummy candidates even grew beards and mustaches for the occasion.

At the very end of 2016, Alexei Navalny announced his intention to run for president, regardless of the law that prohibited candidates with un-expunged convictions from registering. Navalny established a network of regional campaign offices and actively participated in public events. The politician seemed to signal to the authorities that he would participate in the elections no matter what. However, the Kremlin did not follow the old rules; Navalny was not allowed to run in the elections, and an alternative candidate, Ksenia Sobchak, was offered to those who were dissatisfied (she received 1.66% of the votes).

Navalny and his associates did not stop there and continued to promote electoral resistance to the regime, introducing the concept of "Smart Voting." The goal of this strategy was to break the ruling party's overwhelming advantage. In single-mandate district elections, voters were encouraged to support the non United Russia candidate with the best chances of winning as determined by Navalny’s team. In party-list elections, they were advised to vote for a party that wasn’t United Russia but had the potential to pass the electoral threshold, and in gubernatorial elections, they were encouraged to vote for any candidate except the representative of the ruling party. The strategy and its success were assessed differently - thanks to Smart Voting, even candidates who were not entirely aligned with opposition views won, as well as some controversial figures. Nevertheless, it made elections more competitive, and the authorities viewed Smart Voting as another obstacle that needed to be overcome, both through media and coercive measures.

The opposition tried various electoral strategies. A significant success for the democratic movement was the municipal election campaign in Moscow, which took place in the fall of 2017. As a result, independent deputies appeared in almost half of the city's municipalities, and eight districts were entirely cleared of "United Russia" representatives.

However, by 2019, most independent candidates were simply not allowed to run in the Moscow City Duma elections. Mass protests erupted in the capital. On July 27, 2019, more than a thousand people were detained at a protest, and later, a criminal case was initiated for mass riots. In total, 35 people were involved in the "Moscow case," with 22 of them convicted.

In 2020, a constitution amendments referendum – an all-Russian vote on constitutional amendments which, invariably falsified, heralded Russia’s further shift to authoritarianism. The referendum resulted in a many changes, like constitutionally outlawing gay marriage, and defining ethnic Russians as a “state-forming” people, but most importantly it alloowed Putin to run for two more terms. Electoral transformations have brought Russia to a point where the system has become entirely closed, bureaucratic, and aggressively responsive to any form of dissent, even if the dissent is generally loyalist. In 2018, Sergei Furgal was elected as the governor of the Khabarovsk region – a faux candidate who the incumbent regional leader only needed as a formal opponent, like a punching bag. Furgal's victory came as a surprise, as he had conducted virtually no campaign. However, after becoming governor, he seemed to sense a degree of independence and began working to gain the trust of the electorate.

This period of relative independence was short-lived. In the summer of 2020, Furgal was arrested and charged with ordering murders of his business rivals in the 1990s. In Khabarovsk, large-scale regional protests erupted, with thousands of people taking to the streets, initially almost daily and later on Saturdays.

A year later, the intensity of the protests subsided, but in 2022 and 2023, rallies in support of Furgal continued, although much less frequently, and with the participation of significantly fewer people.

Initially, the authorities adopted a wait-and-see approach, waiting for the number of protesters to decrease. They then responded with forceful dispersals, arrests, and administrative offense cases. Nearly 500 administrative cases were initiated, along with four criminal cases. In February 2023, Furgal was sentenced to 22 years in prison.

Despite Russia being engaged in a full-scale war, the electoral cycle continues as scheduled. In 2023, elections for regional legislative assemblies and by-elections to the State Duma to replace deputies who left for various reasons took place on a single voting day. In March 2024, the Kremlin ran their presidential election. Unsurprisingly, Putin was made victor with an unbelievable 87 percent. Monitors, some of whom were detained for as much as wearing a Navalny t-shirt, reported massive violations. The Kremlin utilized everything from bringing in state-employed voters to falsifying electronic votes.

The opposition tried to spoil the Kremlin’s party. They called on everyone to show up on 17 March, the last day of the 3-day voting period, at noon local time and vote for any candidate but Putin or to spoil their ballot. The Kremlin’s response to the noon action was illuminating of its modus operandi. Authorities detained some election monitors and protest voters. A few were fined. One activist’s home was raided because she wrote an anti-war slogan on her ballot. Privacy? Forget about it. In Odintsovo, a small town near Moscow, police surrounded the ballot box checking ballots before they were put in. They seized whatever ballots they did not like. The two vaguely oppositional candidates were demonstratively banned from running.

No serious opposition leader could ever be on the 2024 ballot. Alexei Navalny was killed, weeks before the election. Opposition leaders, and activists are jailed or have emigrated. The few non-systemic politicians remaining in Russia face restrictions and pressure.

The authorities have made fair elections and the participation of independent political parties virtually impossible for so long that now there is simply no chance for free elections.

"There are limits that cannot be crossed. There's a red line. The state shouldn’t be cruel, but it should ensure that everyone follows certain rules," said Vladimir Putin in 2013, when asked about mass protests.

More often than not, protests in Russia have been followed by stricter anti-protest laws. In the summer of 2004, Russia introduced a so-called “notification procedure” for official protests. Although the law states that a person can simply inform authorities about the event, in reality, this is not enough, obtaining a permit is necessary. All "protest" laws are so convoluted that ultimately, everyone involved can find themselves facing criminal charges. To coordinate a protest, organizers have to work through a bureaucratic process involving several government agencies. Protests outside the capital region require even more effort.

Russian authorities and propagandists often refer to Western precedents when discussing protests. When discussing the 2021 pro-Navalny protests, Olga Skabeeva – known as “the iron doll of Putin TV” – compared them to protests in the United States:

"Over the past 16 years, 13 amendments have been made to the laws, step by step restricting the right to freedom of assembly. As a result, any peaceful protest not approved by the authorities has become criminalized," says Peter Frank, one of the authors of Amnesty International’s annual report on human rights in Russia.

"In their country, they call unauthorized actions a rebellion and the participants terrorists. When it comes to Russia, the rhetoric changes dramatically: and the people who beat up the police are called peaceful protesters by the US State Department."

Skabeeva also claimed that if the Navalny protests were to have happened in the United States, the protestors would have been shot for attacking the police.

No matter how hard organizers try to authorise a protest with local authorities, protestors are consistently beaten and arrested. Injuries and unjustified detentions have become routine. Konstantin Konovalov – a Russian graphic designer known to attend protests – was seized by riot police, who broke his leg, hours before a protest. Police harrassed a couple whose child was seen at protests and almost took away their parental rights. Women have been kicked in the stomach and teenagers have been taken to the police station. Such cases can be listed by the dozens. Typically, law enforcement officers are never prosecuted for their brutality.

"What does the current legislation say? You need to obtain permission from local authorities. Got it? Go and demonstrate. If not, you have no right. If you go without it — you'll get beaten with a truncheon. Well, that's it!" - said Putin in 2010.

In the fall of 2004, the Orange Revolution began in Ukraine demonstrating that street protests could lead to a change of government right on Russia’s doorstep, frightening the Kremlin. In January 2005, massive protests started in Russia due to the monetization of benefits. What was most troubling for the authorities was that these protests significantly undermined President Putin's popularity rating.

Fearing an “Orange” revolution in Russia, the authorities began building a public support base. Pro-Kremlin youth movements – primarily "Nashi" – were promoted by the Russian government to counter opposition in the streets.

By the winter of 2011, Russia had experienced several waves of large-scale protests, most notably the "Marches of Dissent" and "Strategy-31". Among the authorities and propagandists, the term “non-systemic opposition” appeared: most of the protestors weren’t registered with official political parties.

The largest protests were held in late 2011 and early 2012 after the State Duma elections. The large-scale demonstrations and vigor of the protestors forced the authorities to acknowledge and engage in dialogue with them. At a rally on Sakharov Avenue in Moscow, Alexei Kudrin – a longtime subordinate of Putin and former finance minister – addressed the protestors. In the winter of 2012, President Dmitry Medvedev met with representatives of the "street opposition" - Sergei Udaltsov, Boris Nemtsov, and Vladimir Ryzhkov. During the meeting, Medvedev announced simplifications in the registration of political parties, which had been restricted in the mid-2000s, and the return of direct elections for governors (although half a year earlier, Medvedev said that they would not be returned “even after 100 years”).

Over the next two years, the protests of 2011-13 became the largest since the fall of the Soviet Union. Russians were outraged by the falsification of results in the 2011 parliamentary elections. Protests were held frequently and were attended by thousands chanting the slogan “For fair elections.” On December 10, 2011, about 100,000 people gathered at the Bolotnaya Square protest. Most were ordinary citizens who came to the protest for the first time in their lives. A fair share of radicals of all stripes showed up too – in neighboring columns one could spot both black-yellow-white "imperial" flags of nationalists and red flags of the Left Front.

Two weeks later, about 120,000 people gathered at the protest on Moscow’s Sakharov Avenue. The stage featured a diverse group of individuals, from actress Lia Akhedzhakova to former Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov, from left-wing activist Sergei Udaltsov to nationalist Vladimir Tor. Two young, promising politicians also spoke at the event: Alexei Navalny and Ilya Yashin. Both were eventually jailed, Navalny in 2021, Yashin in 2022. Navalny was killed by the Kremlin, Yashin is still behind bars.

In February 2012, nearly 120,000 people again gathered at Bolotnaya Square. The authorities, with the help of propagandist Sergei Kurginyan, organized a counter-protest called the "Anti-Orange Rally" nearby. They brought paid state employees to this rally, but fewer people attended compared to the numbers on Bolotnaya Square. However the Ministry of Internal Affairs proudly announced that 138,000 people attended instead of the expected 15,000. Putin, then Prime Minister, personally paid the fine of a 15,000 rubles for exceeding the number of participants allowed at the "anti-opposition" rally.

Beyond Moscow, large-scale protests were held in St. Petersburg, Rostov-on-Don, Yekaterinburg, Voronezh, and many other cities. Besides traditional rallies, unconventional forms of protest were also used. In Moscow, protestors formed a human chain along the entire length of the Garden Ring. The participants wore white ribbons and called the action “The White Circle”. . In response, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin dismissively compared the protest symbol to condoms.

On May 6 and 7 of 2012, the opposition planned the “March of Millions” rally to protest Putin’s inauguration for another presidential term. Although the event was officially approved (after many delays), police began beating the massive column of protestors moving towards the gathering point, Bolotnaya Square. Protestors were beaten with batons, kicked, had their clothes torn, and were forced out of Bolotnaya Square. At least 40 protesters sought medical assistance. According to the state news, 29 law enforcement officers were injured, and four were hospitalized. Official figures state that 436 people were detained. According to OVD-Info's calculations, 566 people were detained.

The "physical injuries" to law enforcement officers were examined during the "Bolotnaya case" - a criminal case against participants in the May 6 protests. The protesters were accused of "damaging the dental enamel of an OMON officer" and "removing an OMON officer's helmet," among other charges. It was later revealed that the injured law enforcement officers received free apartments from the Moscow government. The "Bolotnaya case" marked the first mass prosecution of protest participants in Russia. More than 30 individuals faced criminal charges, and many of them were found guilty and sentenced to prison.

Following the May 6 protests, the authorities significantly increased fines for protest organizers. Fines ranged from 10-20,000 rubles for “violating the procedures for holding a public event.” In cases of harm to “health or property,” fines can be up to 300,000 rubles. Wearing masks at rallies was also banned. The rules for holding solitary pickets were also tightened. Citizens were required to coordinate with the authorities if "several solitary pickets are united by a single organization and a common intent." Furthermore, the pickets must be located at a distance of at least 50 meters from each other. In Moscow they also prohibited protest motorcades.

In 2012-2013, legal proceedings were also opened against protest leaders Alexei Navalny and Sergei Udaltsov. Navalny received a suspended sentence and Udaltsov was sentenced to 4.5 years of imprisonment.

New restrictions were introduced in fall of 2014, six months after the annexation of Crimea. Alexander Sidyakin, a member of the State Duma and one of the initiators of the law on foreign agents, proposed new amendments to the law on protests, citing the need to react to Ukraine’s Euromaidan protests. Among his proposals was “criminal liability for repeat violations of protest legislation,” which was adopted by the Duma.

"Recidivism" in protests was used to justify more severe persecution. From then on, a violation was considered repeated if a person was subjected to administrative liability three times within 180 days. Penalties ranged from fines of 600,000 rubles to five years in prison. The first person convicted under this article was activist Ildar Dadin, who was sentenced to three years in prison in December 2015 for participating in several protests.

Legislators also ensured that there was as little documentation of violent detentions and information about protests as possible. Journalists were required to wear specific identifying marks, such as bright reflective vests. This made it easier for law enforcement officers to locate reporters in the crowd and detain them.

By 2015-16, mass protests on central city squares had virtually disappeared, although local protests continued. However, in 2017-2018, after anti-corruption investigations by Navalny's team, mass protests became common again. In summer of 2019, thousands gathered to protest the authorities’ refusal to register opposition candidates to run in the Moscow City Duma elections in a process rife with violations. On July 14, 39 people were detained at the protests – including five of the candidates disqualified by the Kremlin. Protesters began gathering almost daily. On July 20, 22,000 attended a rally to support the disqualified independent candidates. On July 27, around 1,300 people were detained during the protests, and on August 3, more than a thousand. Another politically motivated legal case began, known as the "Moscow case". 35 people faced criminal prosecution and 22 were convicted.

In that time, authorities started using a new technique — relying on private institutions and government agencies as proxies to filing suits against protesters seeking fines exceeding tens of thousands of dollars. One such example is Mosgortrans which would often file suits against protesters for blocking roads, trespassing and other such minutiae. A year later, a law prohibiting protesters from blocking roads and sidewalks was passed. The law was used against protesters who had to step onto the roadway because the police were blocking sidewalks. They also banned foreign and anonymous support of protests and designated picket queues as “mass actions.”

In 2021, protesters gathered in support of Alexei Navalny. On January 17, 2021, Navalny returned to Russia from Germany, where he had been receiving medical treatment after being poisoned. He was detained at the airport and sentenced to thirty days in jail. While under arrest, Navalny called on his supporters to take to the streets. On January 19, Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation released an investigative documentary about a secret luxurious residence allegedly belonging to Putin and built with corrupt money. In the film, people were urged to join demonstrations on January 23.

The protests took place in more than 120 cities across Russia, and repeat protests occurred on January 31, resulting in a record number of detentions. Later that summer, the authorities provided official statistics, reporting that more than 17,000 people had been detained. This marked the beginning of another mass criminal process against protesters, known as the "Palace Case." 189 individuals in 33 regions of Russia were charged with “violence against law enforcement officers,” “calls for extremist activities,” “incitement to riots,” “involving minors in life-threatening activities,” and for “blocking roads.” Violations of COVID restrictions were also included in the charges.

As the full-scale invasion of Ukraine loomed, virtually any form of protest had already become illegal and was brutally suppressed. Laws enacted over the course of decades had effectively nullified the ability to voice political demands on the streets. Opposition political leaders either left the country, were imprisoned, or faced imminent arrest.

However, on the very first day of the war, thousands of protesters gathered all across Russia. On February 24, 2022, around two thousand people were detained. The Kremlin press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, stated the next day that no one had the right to participate in unauthorized protests. Nevertheless, the protests continued, despite hastily adopted war censorship legislation further strangling the right to protest. According to OVD-Info estimates, over 19,000 have been detained in Russia in connection with anti-war protests thus far.

Mass protests were brutally dispersed, but protesters did not relent. Many of them have since been detained and prosecuted. Several laws have been passed punishing criticism of the invasion, discussing war crimes, and even calling the Kremlin’s “special operation” a war. Despite this, people hold pickets and performances, lay flowers in memory of murdered Ukrainians, or destroy propaganda materials. Wearing a ribbon in the colors of the Ukrainian flag, performing Ukrainian songs, or even a manicure in yellow and blue can result in criminal charges.

Even the smallest actions are harshly persecuted. For example, the artist Sasha Skochilenko replaced supermarket price tags with information about the war . She was sentenced to seven years in prison for spreading "fake news" about the Russian army. The number of criminal cases for taking an anti-war stance is growing every month - as of March 25, 2024, there were 872 defendants in "anti-war cases."

Those who take more radical action against the war have been sentenced to long prison terms under terrorism charges. In 2023, Roman Nasryaev and Alexei Nuriev were each sentenced to 19 years in a maximum security prison for throwing a Molotov cocktail into the military recruitment office in the city of Bakal. No one was harmed and the fire was extinguished by the guard with a five-liter bottle of water. Soon thereafter the State Duma passed amendments to the terrorism law, further tightening the penalties, including life imprisonment.

Nowadays, in Russia, protests in any form are effectively prohibited, but the authorities continue to suppress even the smallest forms of dissent. In 2022, Vladimir Putin signed new restrictions banning protests in airport buildings, railways, bus stations, and ports. Protests are also banned in or near university and school buildings, hospitals, and churches.

In other words, everywhere.

The woman’s name was Galina Pishnyak. Her husband joined @tooltip-propaganda-girkin Igor Girkin’s @tooltip (Strelkov’s) rag-tag group, which had been holding Slovyansk, a small city in the east of Ukraine, from April to July of 2014. Galina was among those who left the town before the Ukrainian military recaptured it. During the next weeks and months plenty of journalists tried to find proof of the “crucified boy”, but no evidence was found. Slovyansk citizens were questioned, but they said that it didn’t happen. The Lenin Square that Galina mentioned doesn’t exist at all.

Russian president Vladimir Putin was asked a direct question about the story by. Ksenia Sobchak during his annual press conference in 2014. The president ignored the question. But the Channel One TV host Irada Zeinalova answered for him. She stated that even if the story is unconfirmed, it’s more important that “those are the genuine words of a refugee”. Galina herself spoke to a journalist from the independent TV Rain seven years later still insisted that her story was true.

The “crucified boy” case became one of the key examples of Russian propaganda, combining all of its defining features: distortions of the truth, outright falsehoods, the “everybody lies” rhetoric, and energetic use of unverifiable statements.

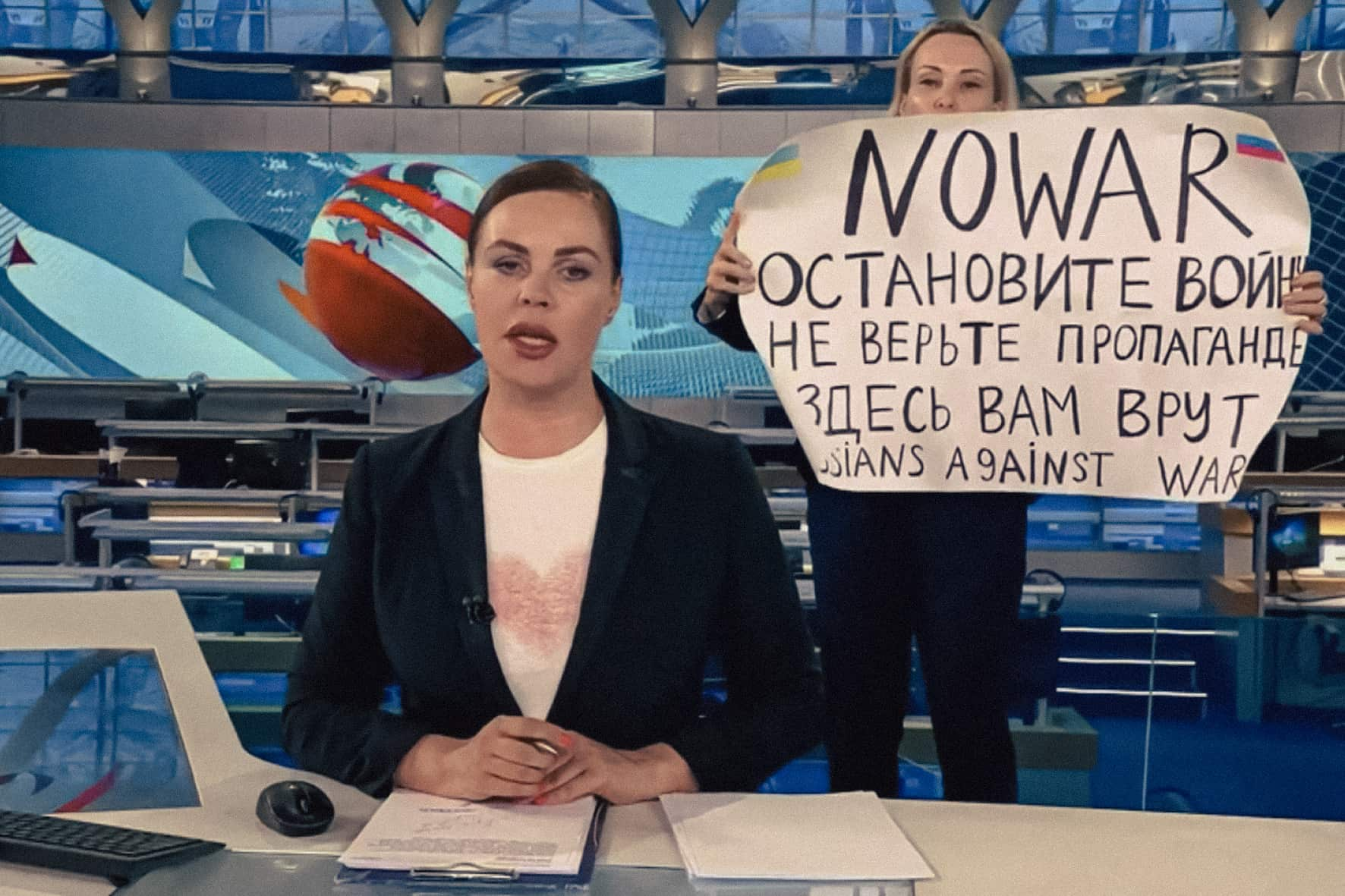

Putin’s regime has controlled the mass media since its early days. They began with expelling Boris Berezovsky from the board of ORT in 2000, seizing and dispersing NTV, and then TV-6. Television has always been a priority to the authorities because that is how most Russians get their information. Control over print media also tightened step by step. But still, even in the late 2000s and early 2010s relative freedom of the press remained. On different TV channels shows covered the protests, and in general could criticize the authorities. There was more freedom in the print press, and on the Internet and radio than on TV. These outlets gave platforms to outspoken critics of the government and published investigations about the authorities.

The situation began to change rapidly after the start of the December 2011 protests. That’s when the process, which Russian journalists called the “fucking chain”, meaning the chain-reaction-like domino effect, began. In 2011-2014, a number of editors-in-chief of Russian media (Kommersant-Vlast, Gazeta.ru, RIA Novosti, Russkaya Planeta, Lenta.ru) were successively fired from their positions. Other media faced severe pressure from the government. For example, the authorities tried to shut down the popular socio-political talk radio station Ekho Moskvy , the main Russian economic newspaper Vedomosti was tormented by endless trials, and TV Rain was kicked off of cable channel lineups for questioning the Soviet Union’s strategy during the WWII siege of Leningrad.

The crackdown was strengthened when the Kremlin turned its attention to the events in Ukraine - the 2014 EuroMaidan, the latest in the string of seemingly successful pro-democracy uprisings threatening the Kremlin’s sphere of influence. The annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbass followed. The Kremlin wanted to not only block a number of opposition publications, but also shape a new aggressive propaganda approach.

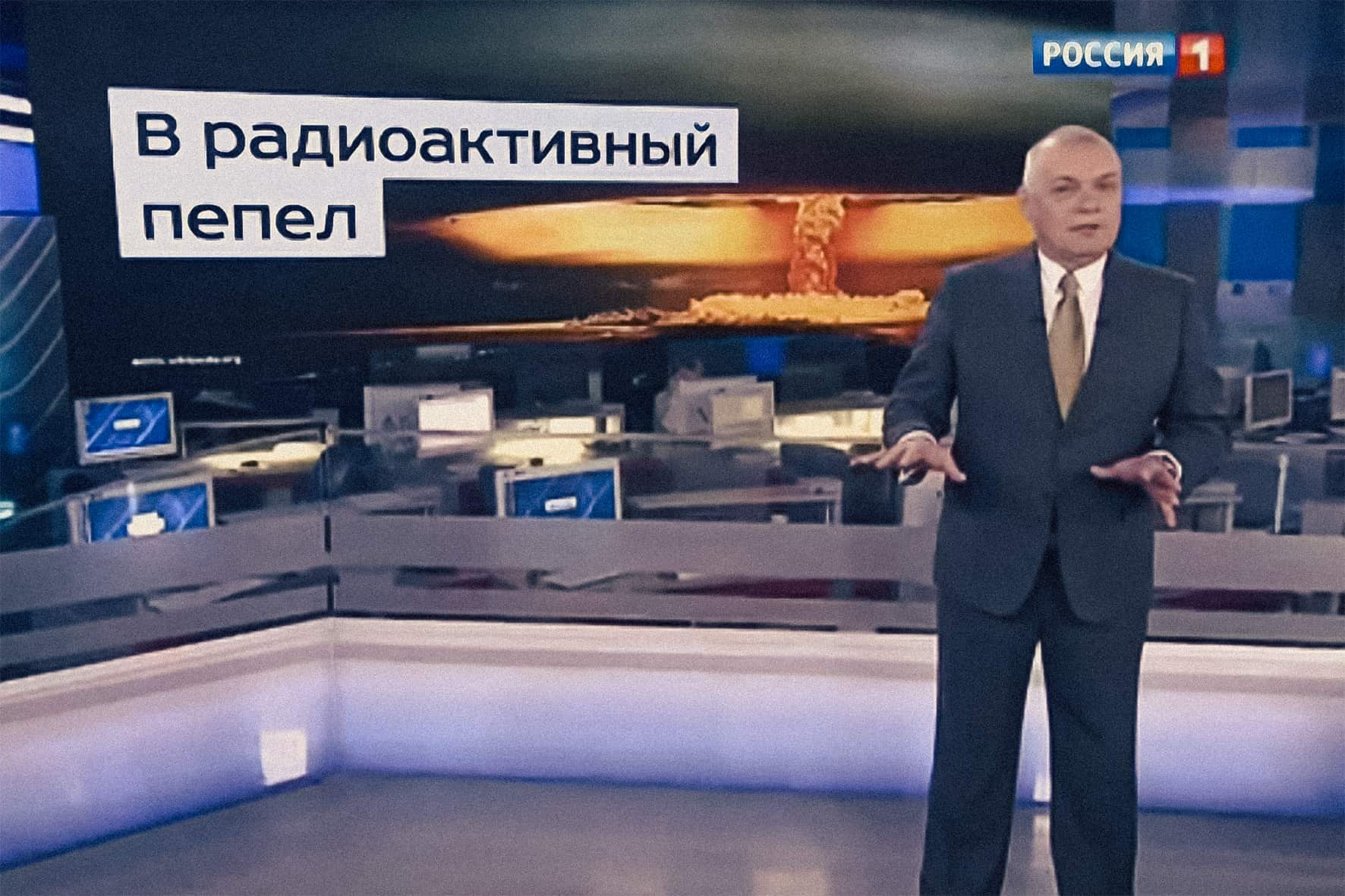

TV turned into the main source of Russian propaganda. Since 2014, Vladimir Solovyov’s late night show, which comes out almost every day and lasts for many hours, has been supplemented with new segments.

For example, “Time Will Tell” with the scandalous host Artem Sheinin. He became famous for walking through the studio holding a bucket with the word “shit” written on it — he said he would pour it onto the heads of Ukrainians.

Also, “60 Minutes” with Olga Skabeeva and Yevgeny Popov. In 2021 Popov became a deputy of the State Duma.

Finally, “Who is against?”, “The Great Game” and even “Moscow. Kremlin. Putin” were added to the evening lineup. “Moscow. Kremlin. Putin” is a program about the things Vladimir Putin has done during the week.

Add to that the state-sponsored propaganda films by the likes of Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Kondrashev and the well-known pro-regime journalist Arkady Mamontov venerating Putin and the annexation of Crimea.

Prior to 2014, Russia already had a tradition of producing propaganda films, for instance, during the height of the 2011–2012 protests, NTV aired a film titled "The Anatomy of Protest" that allegedly revealed relationships between Russian opposition activists and foreign diplomats and spies.

In addition to the "official" channels, several additional propaganda products appeared. In 2008, media manager Aram Gabrelyanov created the "Life" media. Before that, he had published extremely successful publications, mostly devoted to scandalous details about the lives of celebrities.

Now a veritable empire has emerged, from a website to a television channel, later followed by various Telegram channels and new publications. Basically, they were all tabloids - but it was Gabrelyanov who saw the need to talk not only about celebrities, but also about politics, without losing the general TMZ-esque style. Gabrelyanov's media group publications are also famous for their cooperation with the security services and publishing "leaks" from them.

A little earlier, in 2005, Russia launched a television channel designed to "reflect the Russian position on major issues of international politics" and to "inform the audience about events and phenomena in Russian life."

Russia Today or RT, is the channel that began with the ambition of turning into a “Russian BBC” or “Russian CNN” In 2022, it became the paragon of the most obnoxious propaganda, with Margarita Simonyan, RT’s permanent editor-in-chief, as a symbol of deceit.

State news agencies, manufacturing the media narrative, began publishing articles reporting that various foreigners admired Putin's actions or were amazed by Russia's military might (for some reason, the Bulgarians are made out to be the most admiring “foreigners,” which gave rise to the 2020-2021 meme "Bulgarians admired").

Several independent publications have confirmed that, to a large extent, such comments were left by bots paid by the Russian side. And, of course, we cannot forget the troll farms - the largest are associated with Yevgeny Prigozhin; the employees of these "farms," grouped together in one room, were engaged full-time in writing pro-government comments or arguing with political opponents on Russian forums, websites or social networks; the same thing they did and continue to do on foreign sites. Russian propagandists also have been welcoming real pro-Kremlin foreigners – like Tucker Carlson, Scott Ritter and others – to partake in the propaganda.

Another favorite propaganda trick of the Kremlin’s is the use of conspiracy theories. In the summer of 2014 the Malaysian Airlines flight MH-17 was shot down over Ukraine. The Russian state media kept throwing out contradictory versions, from a clumsily doctored photo of a Ukrainian plane shooting a missile at the Boeing to the claims that the plane was stuffed with dead bodies to stage a provocation against Russia. Each of these versions found some followers and undermined any sensible discussion of what happened.

The cause of the MH-17 crash became clear — in general — almost at once, and was investigated in detail by independent media and international bodies. Finally in 2022 the global investigation was affirmed in the judgment of the District Court of The Hague — the civilian jet was shot down from separatist territory, with a Russian missile.

The method of “erosion through conspiracy” has been used many times, especially after the Russian invasion of Ukraine: for example, Russian officials and state media presented the tragedy in Bucha sometimes as the result of the actions of the Ukrainian army, sometimes as a ‘NATO provocation’ and sometimes just as ‘staged scenes created by Ukrainian propaganda’.

Dehumanization of the opposition is also typical; sometimes it reaches the levels that even the propagandists find uncomfortable.

‘Well, they should’ve drowned them. Drowned these children. It’s not your way, you intellectuals and Sci-Fi writers, but it’s our way. Once one of them says that the moskals have occupied (Ukraine), you just go and throw him or her into a rapidly flowing river. <…> Or you could nail them up in their house and burn it up’, said the propagandist Anton Krasovsky, talking to the conservative Sci-Fi author Sergey Lukyanenko, on the state-owned RT Russia channel. These words led to Krasovksy’s dismissal from the TV channel and even a pre-investigative check by the Investigative Committee of Russia (though the investigators did not find any reason to start a criminal case against him).

The language of the propaganda has kept changing and becoming harsher since 2014. The Ukrainians were called ‘ukrops’ (an ethnic slur which uses the first half of the word ‘Ukrainian’ and actually means the dill herb plant) or Banderites, the Russian military personnel that participated in the fighting in Donbas were dubbed “vacationers”, and the separatist battalions from the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, were called “redels”. The propaganda vocabulary also sometimes used the phrases from the other side, such as ‘Buryat tankers’, ‘not-theres’ or ‘orks’.

Several years later, besides the changes in vocabulary, omissions also became widely used. For example, in 2019 many noticed that state media almost never used the word ‘explosion’, calling them ‘bangs’ instead. There are other similar replacements: instead of ‘fire’, state media say ‘smoke condition’ or ‘ignition’, instead of ‘economy shrinking’, sometimes they talk about ‘negative growth’.

With the beginning of the full-scale war all the elements of propaganda that have been constructed since the early 2010s have started working at full throttle, and propagandists no longer mince their words. What Anton Krasovsky said is far from the harshest of things now regularly aired by state media.

As for now, Russia isn’t “literally 1984.” A totalitarian, North Korea-esque mode of censorship is difficult and expensive. What the Kremlin has done is establish legal mechanisms to suppress and punish any anti-regime statements — these laws can be used at the whim of the authorities.

The Russian constitution, in its original 1993 form and even after the 2020 amendments, directly prohibits censorship and guarantees freedom of the press. After decades of Soviet censorship, freedom of speech was declared a universal value in post-soviet Russia. Still, both the state and private interests paid little mind to these lofty principles.

Until the 2000s Russia mostly faced isolated cases of censorship. Then, the regime began a gradual transformation from an unstable democracy to a more rigid authoritarianism. Censorship has always found its place in the political landscape, but it has been impossible to attribute it to a certain person or institution. There was no “Glavlit” responsible for total censorship as there was in the USSR. Various people and organizations have -been involved in censorship. As a result of this joint enterprise, Russia is now a country, where too many things are censored, though no one calls it “censorship”. How is this possible?

Let’s go back in time to February 2012. In Russia, there have already been several months of mass protests. Initially aimed against fraud in the State Duma elections of December 2011, the demonstrations were moving towards new, anti-Putin slogans, and coming up with novel forms of expression. Then-little known punk band Pussy Riot released its music video shot in Moscow’s Church of Christ the Savior – the chief Russian Orthodox cathedral. The band called it a Punk Prayer, with the refrain “Mother of God, drive Putin out!”

Similar things had happened in Moscow before. In 1998, at the “Art-Manezh” exhibition artist Avdey Ter-Oganyan chopped up icons with an axe. In 2000, in front of the public, performance artist Oleg Mavromati nailed himself to a cross, while his assistants carved the words “I AM NOT A SON OF GOD” on his back with a razor. Their performances caused public discontent and even some attempts to criminally prosecute him. But this contributed to the artists’ popularity more than posing a real danger.

In 2012, members of Pussy Riot were found and arrested less than two weeks after their performance. State media launched a harassment campaign. The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) joined in. Formally, the ROC and the state are separate in Russia, but in reality it is the main religion of Russia, receiving a wide range of benefits from the Kremlin.

Tens of thousands of people, organized by the Russian Orthodox Church, participated in a sort of a mass prayer next to the Church of Christ the Savior in Moscow. At the court hearing where the punk-group was on trial, the prosecutor quoted the Trullan Council of the VII century.

Two of three accused, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, were sentenced to two years in prison for hooliganism motivated by religious hatred.

Putin’s reaction was: “To my surprise, the case was hyped up, sent to court, and the court smacked them with a lil’ two year sentence… I had nothing to do with it”. It was this verdict that resulted in the addition of Article 148 to the Criminal Code, “Violating the Right to Freedom of Conscience and Religious Liberty”, often referred to as “offending the feelings of believers”.

Several years later, another high-profile story finalized the repressive union between the state and the Russian Orthodox Church. In 2016, Ruslan Sokolovsky, a youtuber from Ekaterinburg, posted a video of himself playing Pokémon Go in The Church on Blood in Honour of All Saints Resplendent in the Russian Land.

Sokolovsky was arrested. A criminal case was launched against him including nine counts. Sokolovsky was accused of ‘denying the existence of God’ and ‘comparing Jesus to a zombie.’ Public figures spoke out, supporting Sokolovsky and comparing the case against him with the persecution of religious people in the USSR, but to no effect. In 2017, Sokolovsky was given a suspended sentence of 2 years and 3 months, as well as put on the list of terrorists and extremists.

Internet censorship became yet another way the state violates freedom of speech. RosKomNadzor (RKN), a censorship institution created in 2008, gained prominence soon after the 2012 protests broke out. In 2012, RKN, which held little power previously, was granted a powerful tool — the newly-passed law ‘On the protection of children from information detrimental to their health and development’.

Now RKN could limit access to internet resources, creating a blacklist on the grounds of ‘protecting minors’. The passing of this new law led to significant protests from large internet platforms (for instance, a blackout strike at Wikipedia, LiveJournal, VKontakte and Yandex, which yielded no result). Within a year, the State Duma passed another law, giving RosKomNadzor the right to block internet resources without a court order, based only on a directive from the General Prosecutor's Office.

In the 2010’s, the government mostly tried to control freedom of expression; only later did censorship turn into repression of those simply restating information. Radical opposition media became the first victims of the 2012-2013 laws. In spring of 2014, not long before the ‘referendum’ on the annexation of Crimea, RosKomNadzor banned a number of websites: 'Grani.ru' (opposition internet media, founded by the exiled oligarch Boris Berezovsky), 'Kasparov.ru' (the website of a chess Grandmaster and opposition figure Garry Kasparov), Alexei Navalny’s blog in LiveJournal and on the ‘Echo Moskvy‘ website. The new repressive power was used broadly, but in a flexible way. Not every statement resulted in prosecution, but what mattered was that any statement could, if that suit the Kremlin’s interests.

Censorship did not always come directly from the state. Many media suffered from ‘independent decisions’ of their owners. In November 2011, journalist Roman Badanin was fired from his Editor in Chief position at 'Gazeta.ru'. In December 2011 Maxim Kovalsky, Editor in Chief of the weekly newspaper 'Kommersant', was fired as well. In March 2014, Galina Timchenko, the main editor of 'Lenta.ru', was fired from her position, and most of the editorial staff left with her. Every one of these incidents was explained by financial issues, and yet by Putin’s last term the independent media industry had been demolished, in one way or another, almost entirely.

RKN has blocked tens of thousands of internet resources. This practice peaked after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, and the law ‘against disinformation concerning the armed forces of the Russian Federation’ was passed. At the moment, any comment about the actions of the Russian army that does not fit in with the official position of the Ministry of Defence, is branded as disinformation. Even the word ‘war’ itself is illegal to say. Meta and its products have been proclaimed extremist. Access to Facebook and Instagram has been limited by blocks.

The hugely popular messenger Telegram was blocked as early as 2018. The official reason was the refusal of its founder, Pavel Durov, to share encryption keys with the FSB. Eventually, the authorities unblocked the app in 2020, either because of RosKomNadzor’s inability to fight Durov’s VPN features, or because of some arrangement behind the scenes.

Blocking social media clearly divides society into those who are ‘allowed’ to use it, and the rest of the people. State officials like Margarita Simonyan, Duma members, or war propagandists, continue using their accounts on ‘forbidden’ social networks. In spring 2022, Putin’s press-secretary Dmitry Peskov even directly stated that ‘since VPN-services are not banned, using the [blocked services] is allowed.’

One of the methods the Kremlin uses to fight Russian civil society is putting pressure on pro-democracy NGOs strangling activists’ freedom of expression. In 2012, the government passed an amendment to the law “On non-profit organizations”, which introduced the term “foreign agent”. Any person or organization with this status has to add a special label warning of their status to any of their statements, and regularly report on all their activity. Failure to comply with this law risks criminal prosecution. A wide range of actions can lead to you being declared a “foreign agent”, from receiving a few rubles from a foreigner friend when paying at a restaurant to reposting an article written by a foreign agent. At first, society did not really notice these changes in 2012 since they were only applied to NGOs, but the law started working in full force later when it was broadened to include individuals and journalists.

This set of “foreign agent” laws isn’t explicitly linked to censorship, but the practice of declaring an organization “extremist” or “terrorist” became an overused instrument to limit freedom of speech in Russia.

Starting in late 2020, the government began labeling “foreign agent” en masse which led to the closure of some media outlets and a gradual emigration of journalists and activists.

Many who were declared foreign agents did not want to comply with the censorship requirements of these laws, but were also not ready to pay enormous fines and risk imprisonment.

On paper, it may seem that the “foreign agent” restrictions aren’t so bad – you simply need to include a warning paragraph before any text you publish. But in practice, this status leads to people being unable to find a job (like Pyotr Manyakhin, a journalist from Novosibirsk), banned from Russian photo banks (like Taisia Bekbulatova). Many organizations – both public and private – refuse to cooperate with “foreign agents”. There are no explicit criteria that determine what actions make a person a “foreign agent”, while amendments from December 1st 2022 washed away even the existing guidelines. Now anyone can be declared a “foreign agent”.

The people and organizations that decided to stay in Russia and continue their work despite the restrictions constantly face the risk of serious fines or closure, making their work virtually impossible. This happened to the human rights NGO “Memorial” (which was fined roughly 6 million Euros for not labeling their material for 2 years), Siberian news outlet “Taiga.info”, and others. Those who are not yet blocked are constantly paying fines or risk criminal prosecution.

Laws on “fake news” and “discrediting the Russian army”, which were passed soon after the start of the war, became the cherry on top of the Kremlin’s censorship machine. Now, not just interpretation of the facts, but the facts themselves are punishable.

Ilya Yashin, an opposition politician and a municipal deputy, was sentenced to 8.5 years for a YouTube stream about the Bucha Massacre. Meanwhile, Alexei Gorinov, another municipal deputy from Moscow, was sentenced for 6 years and 11 months for making “fake” statements about the war.

Another way to silence people is a new law that bans the “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations”, which was passed recently. This law replaced the 2013 law banning “LGBT propaganda” to minors.

Although this new law was termed an LGBT “propaganda ban”, people are not only prosecuted for LGBT-related content, but for anything regarding discussions of human bodies and sexuality. An example is the multi-year case of Yulia Tsvetkova, an artist from the Russian Far East. In 2019 she was accused of “distributing pornographic material” for posting her body-positive drawings of women on VKontakte. The accusation came from an infamous state-affiliated anti-queer activist, Timur Bulatov. The artist was also declared a foreign agent, had to stay under house arrest, and pay constant fines.

Charges of “propaganda” can be fabricated en masse, and the first cases of censorship are already being enforced. Any books that somehow mention LGBT themes are being removed from bookstores, while books written by “foreign agents” are wrapped in densely sealed packaging and marked “18+”.

"I want to report that the group of @tooltip-siloviki-fsb FSB @tooltip employees sent on a business trip to work undercover in the government is coping with their tasks at the first stage," began the speech by the recent FSB chief and now Prime Minister Vladimir Putin at the celebration of @tooltip-siloviki-chekist-day "Chekist Day" @tooltip in December 1999. Ten days later, he became the acting President of Russia. His address was a typical Putin joke - which turned out to be only partly a joke.

Putin’s rule forced a new word into the Russian vernacular, so pervasive it found its way into other languages as necessary to understand the Kremlin: siloviki. Siloviki (or silovik if singular) can be roughly translated as “enforcers”, and literally it means “men of power”. This term usually refers to representatives of law enforcement agencies, intelligence organizations, armed forces, and other state structures authorized to use force. Throughout Putin’s rule, the Siloviki have slowly gained influence.

In Russia, the word "siloviki" is used very broadly, including in relation to political groups. With the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the dominant position of the siloviki in Russian politics became indisputable. However, this was not always the case; the power of the siloviki was established gradually.

In July of 2010, protesters gathered in Saint Petersburg as part of the "Strategy 31" movement. During the event, a police officer approached protesters, screaming “Who else fucking wants some, you weasels?!” The officer seized a young man and beat him in the head with his baton. At the time, such a blatant and open display of cruelty in a major city was unheard of. This initial instance of police brutality was widely covered across the media. The cop was dubbed the "pearly ensign" because of his wrist bracelet.

It took about a month to identify the silovik. After being found by the St. Petersburg police department, he was reprimanded for violating service regulations. Later, a criminal case was opened against the officer. Many witnesses and victims recognized him at court. Nevertheless, he denied his guilt and was sentenced to a suspended sentence (meaning he wasn’t required to serve real prison time) of 3.5 years.

Year by year, the actions of law enforcement agencies became increasingly harsh. The already light punishments for brutality were phased out entirely. Two years later, the OMON officers who took part in the brutal crackdown on the 2011-2012 Bolotnaya Square protest were given free state-provided apartments, rather than court sentences. The impunity of the siloviki slowly became entrenched, as well as their readiness to resort to cruelty.

The term “Siloviki” entered common usage in the wake of the 1993 Constitutional Crisis, when President Boris Yeltsin’s power was challenged by the Russian parliament. Yeltsin was able to rely on law enforcement agencies (primarily the police and internal troops) in that conflict, suppress opponents, and emerge as the winner, shelling the parliament in the process. Yeltsin won himself a new Constitution that strengthened the president's power and laid the foundation for future authoritarianism.

The power of the Siloviki flourished with Vladimir Putin’s rise to power. Putin himself came from one of the most influential Soviet security agencies, the KGB. While vague, the term “siloviki” often refers primarily to the Federal Security Service (FSB) – the successor of the KGB – and several other special services. Over time, numerous different security structures emerged. For example, in 2016 Putin established the National Guard of Russia, also known as Rosgvardiya. This organization absorbed several old security structures through complex reorganization and is headed by Viktor Zolotov, Putin’s former bodyguard. Rosgvardiya’s authority soon expanded to a wide range of tasks, from dispersing protesters to participating in the invasion of Ukraine.

Among Putin’s agencies, the military was always separate and had less influence despite its elite resources, such as the Main Intelligence Directorate. Attempts by military leadership to gain more political power in Russia yielded no results. General Alexander Lebed briefly gained popularity during the conflict in Transnistria. During the 1996 elections, Lebed helped Yeltsin win by splitting the vote, then dropping out of the race. Afterward, the General’s career declined when he signed the unpopular Khasavyurt accords, ending the First Chechen War, and granting Chechnya temporary quasi-independence. He later served on the Russian Security Council and as governor of the Krasnoyarsk region, but died in a plane crash in 2002.

Another incident concerns General Lev Rokhlin, a Chechen War veteran, State Duma deputy and chairman of the parliamentary defense committee. In 1997, he founded the Movement in Support of the Army, which beckoned military who opposed Yeltsin. There were persistent rumors that Rokhlin was preparing a coup. It is unknown to what extent these rumors were true, but in July 1998, Rokhlin was found dead at his country house in the Moscow region. Officially, his wife was accused of his murder. However, there are still reasons to believe that the killing was related to Rokhlin's political activities.

In 2008, the Center for Combating Extremism (CPE/Center E) was established within the Ministry of Internal Affairs, with offices appearing in each region of Russia. In its early days, this structure primarily focused on combating far-right and far-left movements. However, by the mid-2010s, CPE operatives began targeting peaceful protesters, opposition politicians, and anyone deemed to pose a threat to Putin’s growing authoritarianism. Ultimately, the CPE evolved into a political police force with broad powers and functions, ranging from monitoring protest participants (and instructing riot police) to searching for extremists on the internet.

The siloviki were crucial in suppressing the protests of 2011-2012. In May 2012, one day before Putin's third-term inauguration, clashes occurred on Bolotnaya Square in Moscow and the police brutally dispersed the protesters. Shortly thereafter, the authorities initiated the "Bolotnaya case," accusing peaceful protestors en masse of organizing riots. Many of them were also charged with “using violence against representatives of the state.” The charge has since been used as a common tool to punish protesters. The defendants received varying sentences. Businessman Maxim Luzyanin was charged with "inflicting minor bodily harm on OMON officers," including "damage to dental enamel." He was sentenced to four and a half years imprisonment.

Vladimir Putin learned from the Arab Spring. During protests in North Africa and the Middle East, the police and army often sided with the protesters. Since the start of Putin's third term, budget spending on security agencies has consistently increased. In 2012, approximately 11% of the budget was allocated to national security and law enforcement. In 2019, it rose to 12.5%. While this increase may seem relatively small on its own, combined spending on national security, law enforcement, and defense in 2019 accounted for nearly one-third of all budget expenditures despite the decrease in government revenues from 17 trillion rubles in 2012 to 13 trillion rubles in 2019. For comparison, in 2019, spending on education was around 4% of the budget, healthcare slightly over 3%, and culture approximately 0.7%.

Russia also relies on siloviki from other countries. After the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity, former members of Ukraine’s Berkut special forces unit fled to Russia. Many became Russian policemen or joined special units. Journalists identified Sergei Kusiuk, a former Berkut deputy commander, during the crackdown on Moscow protests in the spring of 2017. He was seen issuing orders over the radio while dressed in an officer’s uniform of the Russian National Guard. Kusiuk, who escaped to Russia via annexed Crimea, is suspected of involvement in the murder of 48 activists and the attempted murder of 80 during Ukraine’s 2014 uprising.

In fall of 2015, the Kremlin launched a military campaign in Syria, which Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu used to bolster the military’s popularity with the public. Putin's government engaged in various forms of publicity, from Shoigu’s “tank biathlons” to expensive propaganda films. One example is Alexey Pimanov’s “Crimea,” which aimed to legitimize the 2014 annexation. In June 2022, the Ministry of Defense established a Fund for the Support of Military-Patriotic Cinema.

In 2012, torture at the Kazan "Dalniy" police department made nationwide news. Officers routinely tortured detainees by inserting champagne bottles, pencils, and mops into their rectums. A case was opened against the station and the verdict was released two years later: some police officers received lengthy sentences, while others were sentenced to 2 to 6 years in a settlement colony, essentially an open jail. The term "nabutylivanie" or “bottling” (a form of torture involving rape with a bottle) became another colloquialism used to describe the actions of siloviki. Torture and killings in police stations were not something new or unique to Kazan – they had occurred in Russia before the "Dalniy" scandal and continue to this day.

Torture has also been consistently used by the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN). The story of inmate Yevgeny Makarov, who was tortured by 18 FSIN employees in a Yaroslavl prison in 2018, gained widespread attention. Lawyers and journalists gained access to detailed video footage of the abuse, allowing society to see how it happens in practice firsthand. In recent years, torture has ceased to be surprising: they humiliate those detained at protests, torture people, and force confessions even in non-political cases. Detainees are routinely subjected to sexual violence. In September 2022, activist and poet Artem Kamardin claimed that he was sexually assaulted with dumbbells during his detention. This was not investigated and no one has been punished.

Each wave of public protests in Russia leads to new cases against participants and harsher treatment of protesters. In addition, the "threat to the siloviki" charge is being used against protesters more than ever. Protesters have been arrested for throwing empty plastic bottles and cups at the police and the police have even sued them for damages. After the large-scale demonstrations protesting corruption in then Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s office, nine people in three cities were accused of “threatening the police.”

For two decades, the Kremlin has been building a dictatorship, supporting and nurturing siloviki, appointing them to important positions, providing them with protection, money, and power. The siloviki have been central to strengthening and preserving Putin’s authoritarian regime.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine was a moment of triumph for the siloviki. After being nurtured by Putin for years, the siloviki became completely loyal to the regime. Initially, they were hesitant to start a war with Ukraine. Over time, however, they began to support a potential invasion. However, the siloviki did not fulfill the Kremlin’s hopes for a quick conquest of Ukraine and are now often under criticism from the "radical patriot" camp, pro-war activists, volunteer fighters, as well as semi-official paramilitary structures.

Nevertheless, the Russian military is still occupied with the war. On the homefront, the police and National Guard have remained to combat opposition and dissent. Law enforcement agencies have proven to be much more effective against their own citizens. Protests against the war are harshly repressed and minor infractions are resulting in cases of "discrediting the armed forces". Frontline soldiers are being hailed as “heroes of the Special Military Operation” and are giving “lessons of courage” in schools.

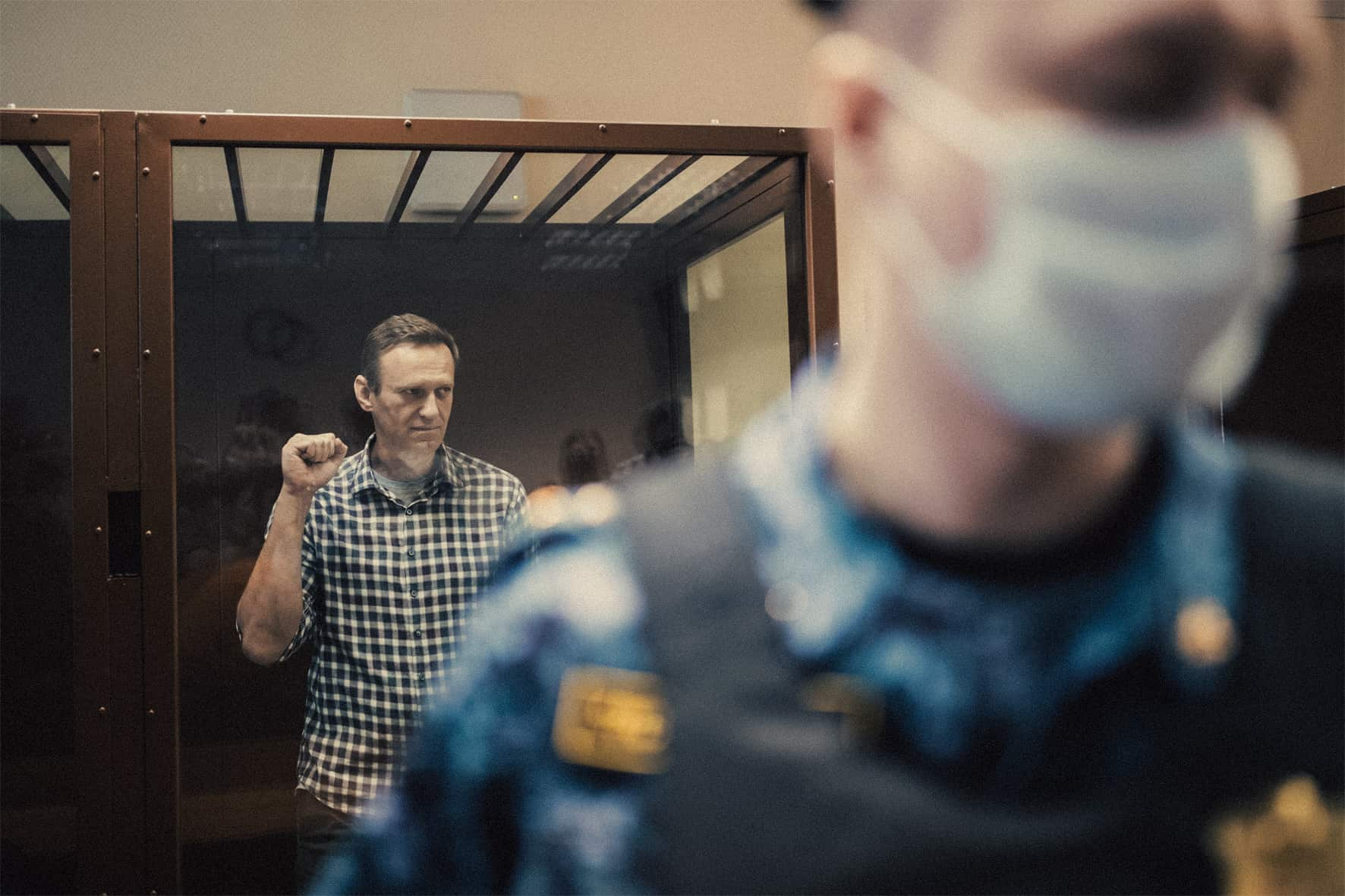

Putin’s government and its siloviki enforcers have remained stable despite the war. The siloviki’s most brazen coup this year was the murder of Alexei Navalny. The Kremlin critic who has been challenging siloviki and Putin for over a decade was killed on the Kremlin’s orders – weeks before the 2024 presidential election.

The authorities saw Alexei Navalny as their main threat. Even before the war in Ukraine, attempts were made on his life. In August 2020, a group of eight FSB operatives poisoned Navalny with a Soviet-era nerve agent “Novichok.” When the politician returned to Moscow after examination and medical treatment in Berlin, he was arrested by the Federal Penitentiary Service before he could leave the airport.

Soon after, the government designated the Anti-Corruption Foundation and Navalny’s team as extremist organizations and began persecuting the politician’s supporters. The former head of the Navalny headquarters in Ufa, a major city south of the Urals, was sentenced to 7.5 years in prison. Her colleague from Tomsk (a city in Siberia), Ksenia Fadeeva, received a 9-year sentence, and the former technical director of the “Navalny Live” YouTube channel, Daniel Kholodny, was sentenced to 8 years. Three of Navalny’s lawyers – Igor Sergunin, Alexey Liptser, and Vadim Kobzev – were detained for participating in an “extremist organization.”

After being arrested, Navalny faced multiple new charges. In August 2023, he was sentenced to 19 years in a maximum security prison colony. While in prison, Navalny was punished with solitary confinement dozens of times. He was kept in a 2.5 by 3 meter cell: stifling in summer, freezing in winter, with a bed that the prison guards kept folded up during the day. In total, Navalny spent 296 days in solitary confinement. On February 16, 2024, he was murdered. The Russian authorities refused to release Navalny's body to his mother for more than a week, trying to force her to agree to a secret funeral. She refused and the funeral took place in Moscow on March 1, with tens of thousands of people coming to say their goodbyes. On the day of the funeral, the press secretary of the Russian President said: “The Kremlin has nothing to say to Navalny’s family on the day of his funeral,” and also warned about the liability for participating in “unauthorized rallies.”

Navalny’s murder emphasizes the danger all political prisoners in Russia now find themselves in. This was a message: the siloviki can treat any opposition member however they like with no consequences. This was a message to the citizens: the siloviki can do whatever they want to the people already in their hands and won’t suffer any consequences for their actions.

What's next?

Russia is currently experiencing an extremely difficult period in its history. Political repression has become so widespread that Vladimir Putin's idea of a senseless fratricidal war has turned into our new reality and trauma for millions of people. The war waged by the Putin regime is a direct consequence of the expansion and intensification of repression and the suppression of political freedoms in Russia. And we know for sure that the current situation continues to deteriorate, moving towards greater harshness, cruelty, and mass repression. However, the current situation is not the worst in Russia's history; there have been even darker times. It is a period that the Russian leadership wants to return to.

Russia can already be called a repressive state. Yes, these are not yet Stalinist repressions, but what lies ahead for us? Will Russia return to totalitarianism? Can we reverse this movement?

We don't know.

But what we do know for sure is that if the fight against repression does not stop or weaken it, our work at least slows down its development. And we believe that increasing society's awareness and mounting pressure on repressive mechanisms can lay the foundation for systemic changes in Russia. Therefore, now, more than ever before, it is important to support human rights organizations, independent media, and everyone contributing to the fight for human rights and democracy. Thanks to your support, we believe we can reverse the trend towards totalitarianism and pave the way for a free society where war and repression will only be a bitter lesson in history.